Secrets of Birds’ Remarkable Hearing

Let’s imagine an owl that, in the middle of the night, flawlessly locates a mouse rustling in the leaves. Or a nightingale whose song echoes through the forest and flawlessly reaches the ears of a potential mate. How is it possible that birds, despite lacking visible ears, hear so perfectly? The answer is surprising, and their hearing is a true masterpiece of nature. At the end of the article, you will find a podcast on this topic.

Do Birds Have Ears?

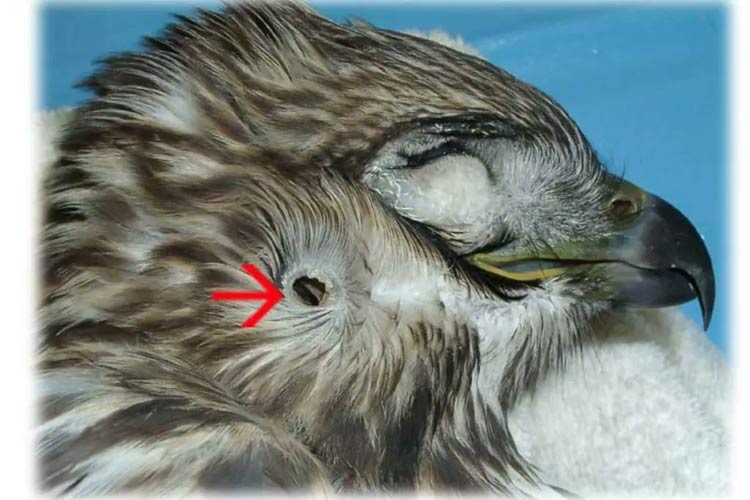

Yes — though they don’t resemble ours. Birds do have ears, but not in the conventional sense. Similar to humans, they are equipped with an outer ear, middle ear, and inner ear. But they differ from humans and mammals in general in that they lack an external ear structure. Instead, they have funnel-shaped ear openings located on both sides of their head, usually situated just behind and slightly below their eyes.

Instead of external pinnae (ear flaps), birds have auditory openings, hidden under feathers. These are small, discreet holes on the sides of the head that effectively collect sounds while also protecting the ear from dust, water, and wind. In some species, such as the Tawny Owl (Strix aluco), these openings are asymmetrical — one is located higher than the other. This allows the owl to locate sounds with almost surgical precision. And those feather ‘ear tufts’ that we see on its head? They are ornaments — they have nothing to do with hearing!

Range of Bird Hearing

Most birds hear sounds ranging from approximately 100 Hz to 8 kHz, although some species can hear even higher frequencies – for example, the Canary up to 10 kHz, the House Sparrow up to 11.5 kHz, and the Long-eared Owl (Asio otus) up to 18 kHz. Birds’ greatest hearing sensitivity falls within the 1–4 kHz range. Birds do not hear ultrasounds above 20 kHz.

How Does Bird Super Hearing Work?

Bird hearing is not a coincidence, but the result of excellent evolution. Here’s how nature solved it:

Anatomy Refined to Perfection

The bird’s ear consists of the ear opening, the middle ear with the eardrum and a single bone (columella), and the inner ear with the cochlea. Although this system is simpler than in mammals, it functions exceptionally efficiently. Owls have an additional advantage: the facial disc, a ring of feathers that acts like a parabolic antenna, focusing sounds and directing them straight to the ears. This is a natural microphone with high sensitivity.

Sensitivity Worthy of a Detective

Birds of prey, such as the Eurasian Sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus), can hear sounds of low intensity below 0 dB*, meaning they can detect even the rustling of leaves moved by small prey in complete silence. Their brain analyzes the differences in the time the sound reaches each ear and its intensity, allowing them to locate the sound source with an accuracy of a few degrees. Owls can track prey almost solely by hearing, even in complete darkness.

* Birds of prey, such as the Eurasian Sparrowhawk, have a hearing threshold in the range of approximately 1–5 kHz, with their hearing sensitivity usually falling within the range of about 0 to 20 dB SPL (Sound Pressure Level), and at some frequencies even below 0 dB SPL. However, this does not mean they hear sounds with an intensity ‘below 0 dB’ in an absolute sense – 0 dB SPL is a conventional reference threshold for audibility, and negative values indicate very high sensitivity, close to the limit of sound detection.

Hearing Tuned to Lifestyle

Humans hear sounds in the range of approximately 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz (20 kHz). Songbirds, such as the Common Nightingale (Luscinia megarhynchos), have particularly sharp hearing in the range of 1 kHz to 4-5 kHz — which is the range in which their own trills resonate. This allows them to communicate effectively over long distances.

Seabirds, such as the Sooty Shearwater (Ardenna grisea), detect infrasound, which helps them navigate over the ocean, sensing approaching storms.

Forest birds, such as the Spotted Flycatcher (Muscicapa striata), are, in turn, sensitive to tones that best penetrate dense foliage. The Skylark (Alauda arvensis), living in open spaces, hears high tones better, which travel unobstructed across meadows.

Evolution as an Engineer

Each bird species has adapted its hearing abilities to its environment and lifestyle. Nature, like a skilled sound engineer, has refined their “audio systems” over millions of years so they are perfectly tailored to their needs.

Asymmetry: An Advantage

In some owl species, especially those that hunt exclusively at night, such as the Barn Owl (Tyto alba) and the Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus), nature has gone a step further, perfecting their “audio system.” Their ear openings are positioned asymmetrically — one is located higher than the other. This is not a coincidence. Thanks to this asymmetry, the owl can determine not only the direction the sound is coming from, but also its elevation relative to itself.

For example, in the Barn Owl, the left ear opening is positioned higher, so sounds coming from below are better heard in the right ear. The owl’s brain instantly combines these signals and creates a spatial image of the prey’s location, even in complete darkness.

Interestingly, those “ears” on top of the head that we see on some owls are actually tufts of feathers that have nothing to do with hearing. They serve visual functions — helping with camouflage and communication with other individuals.

Why Is This So Remarkable?

Bird hearing is not just a curiosity — it’s key to their survival. Thanks to it, they locate prey, recognize mates, warn each other, and navigate over vast distances. What’s more, birds possess the ability to regenerate hair cells (auditory cells) in the inner ear, something we humans cannot do. This means their hearing remains functional even after injuries or in old age.

So, the next time you hear a blackbird singing in the park or see an owl gliding in the twilight, remember: it’s not just the beauty of nature, but also an example of acoustic mastery, honed over millions of years of evolution.

Podcast: Do Birds Have Ears? The Mystery of Bird Hearing

Listen to the podcast where we introduce the mysteries of bird hearing, explain the differences between hearing in birds and humans, and discover whether birds have ears.

Recommended

- African lion

- Asian lion

- African elephant

- African forest elephant

- Asian elephant

- Moose

- Owls

- Parrots

- Giraffe

- Gorillas

- Zebroid

- Zebra

- Giant anteater

- Lizards

- Toucans

- Lemurs

- Secretarybird

- Ants