The Oldest Traces of Art – Voice of the Past on Rock Walls

Cave Paintings

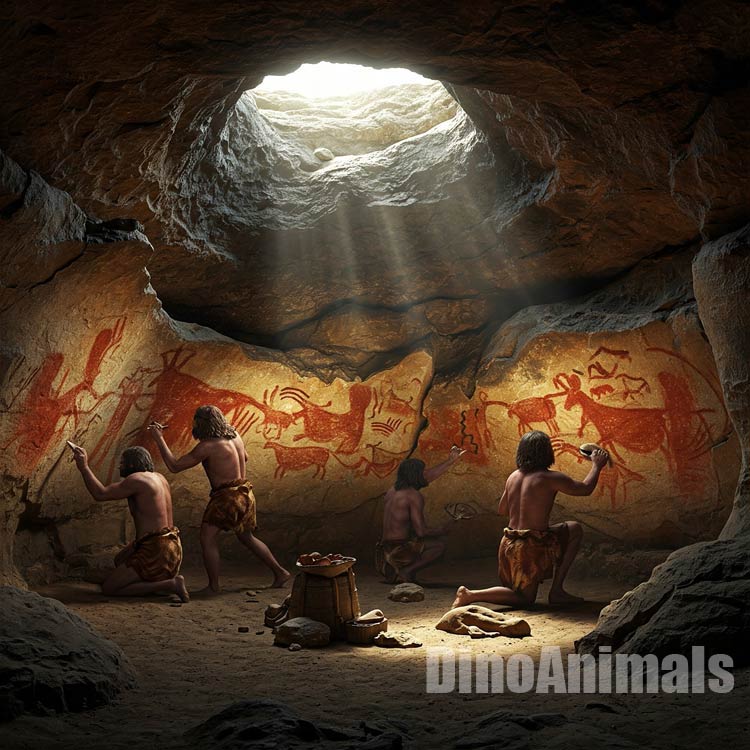

Imagine the darkness of a cave, where the only light is the flickering flame of a torch. In this semi-darkness, tens of thousands of years ago, a human hand touches the cold rock, leaving a trace – a red imprint that will survive for centuries. Somewhere nearby, on the uneven walls, silhouettes of animals appear: galloping horses (Equus ferus), powerful bison (Bison bison), and even extinct woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius), captured in such realistic motion that they seem to come alive in the firelight.

This is not a scene from a movie – it is the reality of Paleolithic artists whose works, hidden in caves around the world, still speak to us from the depths of prehistory. Cave paintings, the oldest traces of human art, are not just pictures – they are a time capsule that allows us to glimpse into the minds of our ancestors. What are they trying to tell us?

Beginnings in the Shadow of Caves

The oldest known cave paintings date back over 45,000 years. On the Indonesian island of Sulawesi, in the Leang Tedongnge cave, archaeologists discovered an image of a wild boar (Sus scrofa), painted with red ochre. This unassuming animal, captured in simple lines, is one of the oldest pieces of evidence of human creativity.

Slightly younger, but equally astonishing, are the paintings from the El Castillo cave in Spain – red disks and handprints dated to 40,800 years ago. In Europe, in the Chauvet Cave in France, works dating back 36,000 years were created: hundreds of animals – lions (Panthera leo), rhinoceroses (Rhinocerotidae family), bears (Ursidae family) – painted with a precision that astounds contemporary artists. These images are not random. They are evidence of something greater – the birth of art, and perhaps even the human soul.

Wandering into the depths of these caves, we feel a thrill of emotion. How is it possible that people who fought for survival in the harsh world of the Ice Age found the time and energy to create? And why did they do it in places so difficult to access, often in narrow, damp corridors where every movement required courage? The answers lie in the paintings themselves – in their themes, techniques, and mysterious context.

The Sistine Chapel of Prehistory

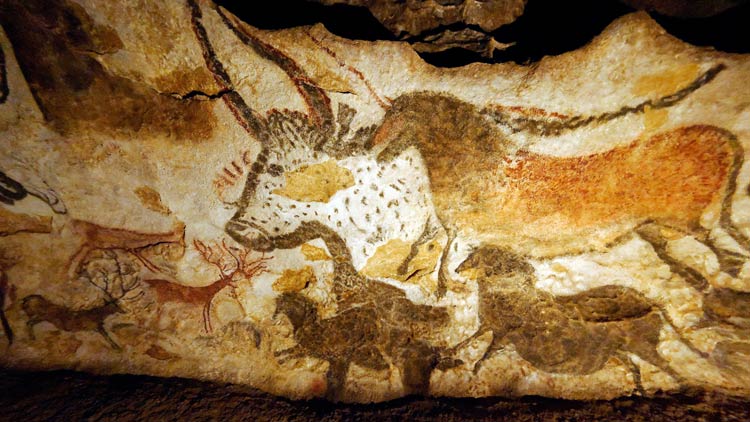

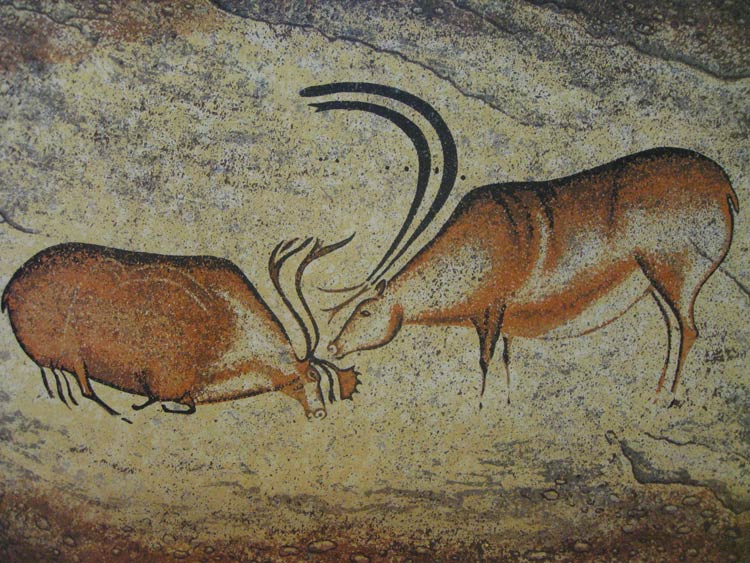

Let’s step into the Lascaux Cave in France, known as the “Sistine Chapel of Prehistory.” Discovered in 1940 by a group of teenagers, it conceals over 600 paintings and thousands of engravings. On the walls of the “Hall of the Bulls,” gigantic animals – some five meters (approximately 16.4 feet) long – seem to gallop in the glow of flickering lights. Paleolithic artists masterfully used the natural bulges of the rocks to give their works a three-dimensional quality. A horse with its head raised, a bison with its head lowered – these images are not static. They live, pulsate with movement, as if they wanted to tell a story of a hunt, a fight, or a ritual.

The technique of these artists is astonishing. They used natural pigments – red ochre from iron oxide, black charcoal – mixed with water or animal fat. Sometimes they blew paint through bone tubes, creating delicate outlines, sometimes they imprinted their hands, leaving a personal signature.

In the Altamira cave in Spain, the bison paintings are so realistic that their authenticity was initially doubted – how could “primitive” people achieve such a level? Today we know that these “primitive” creators were geniuses of their time.

A Spiritual Dance on the Walls Why did they paint?

This is a question that has puzzled archaeologists and anthropologists for decades. One theory suggests that caves were sanctuaries – places of rituals, where shamans went into a trance, and the images of animals were meant to invoke their spirits.

In the Trois-Frères cave in France, there is an enigmatic figure: half human, half deer (Cervus elaphus), with antlers on its head. Is this a shaman during a ceremony? Or perhaps a symbolic connection between humans and nature? In Chauvet, lions and rhinoceroses, painted in dynamic poses, may have been part of hunting magic – an attempt to “capture” the power of animals before the hunt.

Other paintings, such as abstract signs – dots, lines, zigzags – suggest something more: the beginnings of symbolic language. In the Blombos Cave in South Africa, dated to 70,000 years ago, pieces of ochre with engraved patterns were found – perhaps the prototypes of later pictograms.

Was cave art a form of communication? A way to pass on knowledge, mark territory, or build bonds within a group? Each theory opens new questions, and the answers still elude us like shadows in the torchlight.

The Diversity of Prehistoric Cultures

Cave paintings are not uniform. On each continent, they differ in style and subject matter, revealing the richness of prehistoric cultures. In Australia, in the Kimberley region, Aboriginal paintings dating back tens of thousands of years depict mysterious figures called “Wandjina spirits” – humanoids with large eyes and halos around their heads.

In South America, in the caves of Brazil, hunting scenes and geometric patterns dominate. In Europe, animals reign supreme, but in Indonesia, alongside pigs, handprints appear – as if the artists wanted to shout: “I was here!”

This diversity shows that art was not a one-time invention. It developed independently in different corners of the world, reflecting local environments, beliefs, and needs.

In the caves of Sulawesi, traces of ropes and tools were also found, suggesting that painters climbed the rocks to reach their “canvases.” This was not a random pastime – it was an effort that required planning and determination.

Echoes of the Past

Standing before these paintings, we feel a connection with people who lived in a completely different world. They had no writing, cities, or machines, but they had something that defines us as a species: the need to create. Their art has survived for thousands of years – longer than the pyramids, longer than any modern building. But time and nature are not kind.

In Lascaux, the cave was closed to visitors because the breaths of tourists caused mold to grow, destroying the paintings. In Altamira, humidity threatens the colors. These works, although durable, are fragile – like the memory of our ancestors.

What do cave paintings tell us today? That art is older than civilization, that it is born from the human need to understand the world and leave a trace. They are not just images – they are voices from the past that whisper about hunts, rituals, and dreams.

Gazing at these walls, we cannot resist the question: what will we, the people of the 21st century, leave behind? Will our works stand the test of time, just like those red hands and galloping horses? The answer may lie in another cave, still waiting to be discovered – in the darkness that still holds secrets.

The Most Famous Rock / Cave Paintings

A review of the most famous cave paintings that delight and inspire:

- Lascaux (France)

Discovered in 1940, called the “Sistine Chapel of Prehistory.” The “Hall of the Bulls” presents gigantic animals – horses (Equus ferus) and bison (Bison bison) – five meters (approximately 16.4 feet) long, brought to life by the natural shapes of the rocks, dating back 17,000 years. - Altamira (Spain)

Known for its bison (Bison bison) painted 16,500 – 14,000 years ago. The multicolored, realistic outlines are astonishing in their detail – initially, it was doubted that they were the work of “primitive” people. - Chauvet (France)

Treasures from 35,000 years ago – lions (Panthera leo), rhinoceroses (Rhinocerotidae family), and bears (Ursidae family) in dynamic poses. The precision and movement in these images astound even contemporary artists. - Sulawesi (Indonesia)

In the Leang Tedongnge cave, the image of a pig (Sus scrofa) from 45,500 years ago is one of the oldest works of art. The simple, red outline holds enormous significance for the history of creativity. - Kimberley (Australia)

Aboriginal paintings of “Wandjina spirits” – humanoids with large eyes and halos. Dated to thousands of years ago, they introduce us to the mystical world of indigenous cultures’ beliefs.

Rock / Cave Paintings – Interesting Facts

Cave paintings hold not only beauty but also surprising stories that bring the prehistoric world to life. Here are some interesting facts:

- Children as artists

In the Rouffignac Cave in France, handprints and simple drawings were found that – as researchers suggest – could have been the work of children. Some traces indicate five- or six-year-olds, showing that art was part of the life of entire communities. - Painting in the dark

Many paintings, such as those in Lascaux or Chauvet, were created in deep, inaccessible parts of caves. Artists worked by the light of torches or animal fat lamps, which required not only talent but also courage – after all, cave bears (Ursus spelaeus) lurked in the darkness. - The first “animations”

In caves such as Altamira, animals often have additional legs or heads in different positions. In the flickering torchlight, this could have created an illusion of movement – perhaps the oldest form of “cinema” in history. - The mystery of handprints

In the Gargas cave in France, many handprints have missing fingers. Is this the result of a ritual, amputation, or deliberately folding fingers in a gesture? These “mutilated” traces from 27,000 years ago still spark debate among scientists. - Sounds of caves

Acoustic research in caves, such as in Isturitz in France, has shown that places with paintings often have a unique echo. This suggests that art may have been part of rituals with music or singing, enhanced by the natural acoustics.

These curiosities remind us that cave paintings are not just images – they are fragments of life, full of mysteries that still await full explanation. Every trace on the rock is an invitation to travel deep into human history.

Recommended

- Number of neurons

- Homo sapiens

- Charles Darwin

- Dian Fossey

- Jim Corbett

- Jane Goodall

- Human brain evolution

- Evolution theory

- Man a Social Being

- Why did humans lose their hair

- Sexual dimorphism