Megafauna – Why Did Cave Lions and Leopards Go Extinct in Europe?

Secrets of the Ice Kingdom

Imagine Europe tens of thousands of years ago – a frozen, wild land where glaciers sculpted the north, and vast steppes stretched across the south, teeming with life and danger. Amidst the biting frost and rustling grasses, the shadows of big cats lurked – cave lions, rulers of the tundra, with massive paws and eyes piercing the fog, and leopards, agile spirits of rocky hideouts. These predators were the kings of the Pleistocene, the Ice Age, when the world looked like it was from another planet: mammoths roamed in herds, woolly rhinoceroses cut across the horizon, and humans were just beginning their ascent to the top.

But this icy paradise did not last forever. In the blink of an eye – a geological blink that changed everything – the climate warmed, the megafauna began to disappear, and human fires lit up the darkness of caves. What happened to the cave lions and leopards that once ruled Europe? Why did these fearless predators, capable of bringing down a mammoth or outsmarting a deer, vanish without a trace? The answer lies in the fascinating story of the end of the Ice Age – a tale of change, competition, and the fragility of even the most powerful kingdoms of nature. Let us delve into this lost world and discover what swept the big cats off the face of our continent.

Chapter 1: The Ice Age – World of Big Cats

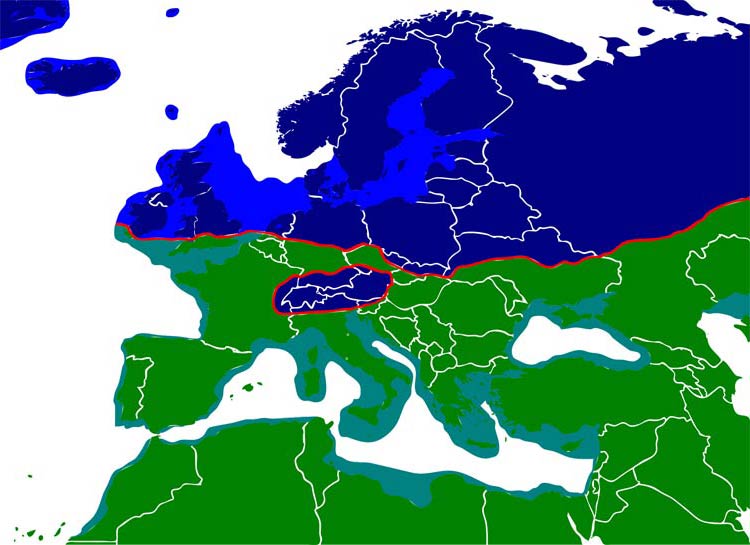

The Pleistocene, spanning from 2.58 million to 11,700 years ago, was an era of extremes. The Earth was cyclically bound by ice sheets, and between successive glaciations, short periods of warming occurred. In Europe, especially during the last glaciation known as the Würm (115,000–11,700 years ago), the landscape was dominated by glaciers in the north and vast steppe-tundras in the south – cold, dry plains covered with grasses, mosses, and low shrubs.

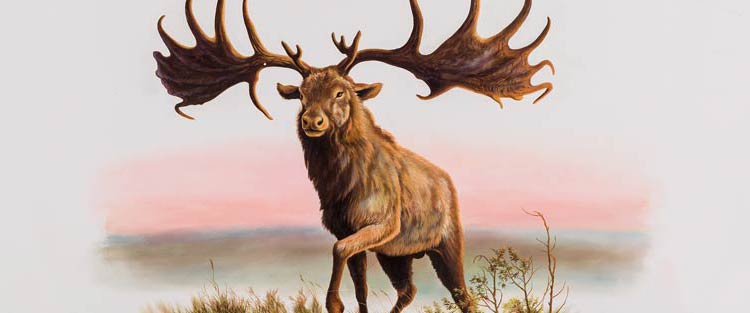

This harsh environment became home to megafauna: mammoths, woolly rhinoceroses (Coelodonta antiquitatis), steppe bison/steppe wisent (Bison priscus), and Irish elk/giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus). And among them, the big cats reigned – cave lions (Panthera spelaea) and leopards (Panthera pardus). In Poland, leopard fossils were discovered in the Biśnik Cave and the Radochowska Cave.

Cave lions, more massive than today’s African lions, were apex predators, hunting large prey – from reindeer to young mammoths. Leopards, more adaptable, lurked in rocky or forested areas, hunting smaller mammals such as chamois or deer. The Ice Age was their time – but also a time that heralded their end. The end of the Pleistocene, around 12–10 thousand years ago, brought changes that forever altered Europe and the fate of these majestic animals.

Chapter 2: Climate Change – The End of the Cold Paradise

At the end of the last Ice Age, Earth’s climate began to warm rapidly. Between 14,000 and 11,700 years ago, temperatures rose by as much as 5–10°C (41-50°F) in just a few centuries. Ice sheets melted, sea levels rose, and the steppe-tundra – the heart of the Pleistocene ecosystem – gave way to dense deciduous and coniferous forests. This transition, known as the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, was a revolution in the natural world.

For cave lions, these changes were a disaster. Their lives depended on open spaces where they could track and hunt herds of herbivores. The forests that encroached on the tundras restricted their hunting territory and hindered effective hunting. Leopards, although better adapted to diverse environments, also lost their niches – rocky hideouts and open areas, ideal for ambushes, became increasingly rare.

The warming also brought another effect: a change in fauna. Cold-adapted species, such as mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses, began to disappear, unable to survive in the new conditions. For big cats, who fed on these giants, this was the final nail in the coffin. The climate that once favored their dominance now turned against them.

Chapter 3: Megafauna Extinction – Starvation of Predators

The Pleistocene megafauna was the foundation of the big cats’ diet. Mammoths, weighing several tons, provided cave lions with enormous amounts of meat. Steppe bison and reindeer roamed the steppes in large herds, and giant deer offered a substantial meal. But at the end of the Pleistocene, these species began to go extinct – some due to climate change, others under the pressure of new arrivals: humans.

The steppe-tundra, which enabled the existence of such herds, was disappearing, giving way to forests where herbivores did not have enough food. Mammoths lost their grassy pastures, woolly rhinoceroses could not cope with the warmer climate, and the number of steppe bison decreased.

Cave lions, specialized in hunting large prey, were unable to switch to smaller animals, such as hares or birds, which began to dominate the new ecosystems. Leopards, although more adaptable, also felt the decline in the availability of medium-sized prey.

Without megafauna, the big cats faced the specter of starvation. Their populations shrank, and the lack of food became one of the main reasons for their extinction.

Chapter 4: Humans – The New King of Europe

Around 40,000 years ago, Homo sapiens appeared in Europe – an intelligent and efficient hunter who quickly became a competitor for the big cats. Humans hunted the same prey as cave lions and leopards: mammoths, bison, deer. Armed with spears with flint tips and using group hunting strategies, they were lethally effective. Every animal hunted by a human meant less food for the predators.

Competition was not everything. Cave lions and leopards could be seen as a threat – to humans, their settlements, or the herds of animals they began to domesticate. Archaeological finds, such as lion bones with cut marks in caves, suggest that humans sometimes hunted these cats themselves, perhaps for their hides or in competition for territory. In later periods, when humans began to transform the environment – e.g., clearing forests for settlements – the habitats of big cats shrank even further.

Humans not only took away food but also actively changed the rules of the game, becoming the dominant predator of Pleistocene Europe.

Chapter 5: Genetics and Lack of Flexibility – Internal Weaknesses

Not only external factors determined the fate of the big cats. Genetic studies show that cave lions had relatively low genetic diversity even before their extinction. This meant less resistance to diseases, environmental changes, or other stresses. When the climate warmed and the megafauna died out, populations with a limited gene pool had difficulty adapting to the new realities.

Added to this was their specialization. Cave lions were machines for hunting megafauna – powerful but inflexible. Unlike wolves or lynxes, which could feed on smaller animals and survive in forests, lions could not change their strategy. Leopards, although more versatile, also had limits to adaptation – forests did not favor their hunting style.

In the rapidly changing world of the Pleistocene, the lack of plasticity became a death sentence for these predators.

Chapter 6: Traces of the Past – What Remains of Them

Although cave lions and leopards disappeared from Europe, they left behind certain traces. In caves, such as the Bear Cave in Poland or Chauvet in France, we find their bones and cave paintings that depict these animals in all their splendor. These pieces of evidence remind us of their former power and of a world that once existed.

Their extinction around 12–10 thousand years ago closed a chapter of the Ice Age in Europe. But their story is more than just a tale of an end – it is a lesson about the fragility of ecosystems and how changes, both natural and human-induced, can alter the fates of even the most powerful creatures. Dinosaurs “know” something about this 😉