Moa (Dinornithiformes) – giant birds

Moa (Dinornithiformes)

It had an extremely important role in its ecosystem, yet we only learned that when it became extinct. Its disappearance from the animal kingdom was followed by the extinction of another, equally fascinating bird species – the Haast’s eagle, which diet was based on moas.

Classification

- Kingdom: Animalia

- Phylum: Chordata

- Clade: Dinosauria

- Class: Aves

- Infraclass: Palaeognathae

- Clade: Notopalaeognathae

- Order: †Dinornithiformes

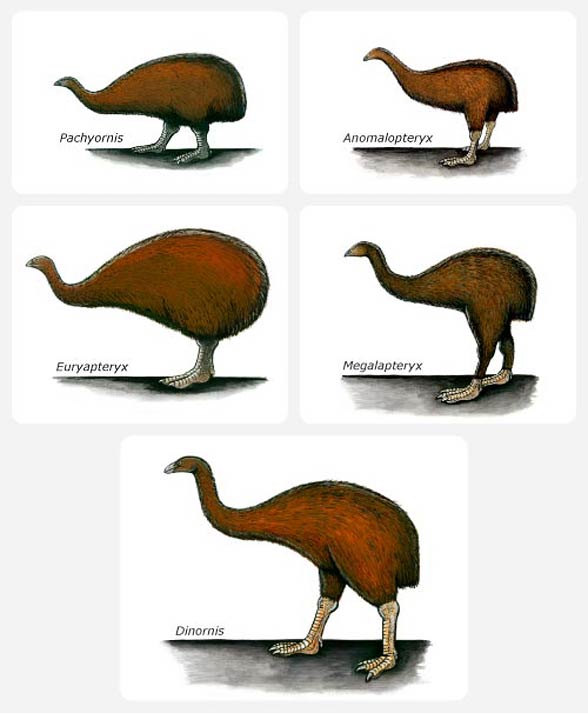

There are 9 species in this order, grouped into 6 genera, all endemic in New Zealand. Species Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezealandiae are the largest birds in the order.

Genera:

- Dinornis

- Anomalopteryx

- Megalapteryx

- Pachyornis

- Eurypteryx

- Emeus

The Dinornis genus involves:

Dinornis genus

- South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus, Dinornis giganteus, Dinornis struthoides)

- Slender moa (Dinornis torosus)

- North Island giant moa (Dinornis novaezealandiae)

- Dinornis gazella

- Dinornis ingens

Moa – discovery and classification

The western biologists have learned about the existence of moa in 1840 thanks to a naturalist Richard Owen shortly after he saw a bone fragment of this giant flightless bird with his own eyes. Over the next 8 years he gave names to 13 different species. Their size and variety within a relatively small habitat was called a natural wonder. In 1907 Walter Rothschild enlisted 38 species of moa birds in the book Extinct birds.

In the 20th century the classification was slightly modified – Gilbert Archey, Walter Oliver and later, Joel Cracraft have changed the list of the species as the individual disparity determined by inhabited region was better investigated, as well as the observed sexual dimorphism. Both of these factors have lead to a shortening of the species list: in 2000 there were 11 species in the record (grouped in 6 genera), yet the number dropped to 10 in 2006.

Areas of occurrence

New Zealand – South Island

The found bone remains inform us which habitats were preferred by moa species. The first list captures the New Zealand’s South Island species and their occupied habitats:

- Bush moa (Anomalopteryx didiformis)

- South Island giant moa (Dinornis robustus) – the western coastal areas covered with rainforests and southern beeches (Nothofagus)

- Euryapteryx gravis, Dinornis robustus, Pachyornis elephantopus, Emeus krassus – the dry forests and shrubberies of the eastern parts of Southern Alps

- Upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus), Pachyornis australis – the Alpine region

The most rare moa species

The most rare species of moa birds was the Pachyornis australis, whereas the upland moa turned out to be the most common species of all, its bones found in the subalpine zone. It could also live in close proximity to the sea, on rocky, steep slopes (Punakaiki – a town on the western coast and central Otago).

New Zealand – North Island

Much less is known about moa habitats on the North Island due to lack of meaningful finds. However supposedly their preferences concerning habitat were similar to their southern cousins’.

Most species lived only on one island (apart from Euryapteryx gravis and bush moa), due to raising water level in the Cook Strait over the millennia, which led to the disappearance of the natural bridge between two islands.

On the whole North Island these birds chose mostly dry grasslands, shrubberies and woods. These areas were inhabited by the following species:

- Euryapteryx curtus

- Pachyornis geranoides

For thousands of years these giant flightless birds were dominant herbivores in New Zealand’s bush and forest ecosystems, until the arrival of the Maori people in the 13th century, when they proved to be easy game for the newcomers.

Until that, moa had had only one enemy – the Haast’s eagle, but due to excessive hunting and loss of habitats the bird became extinct in the 14th/15th century.

Characteristic

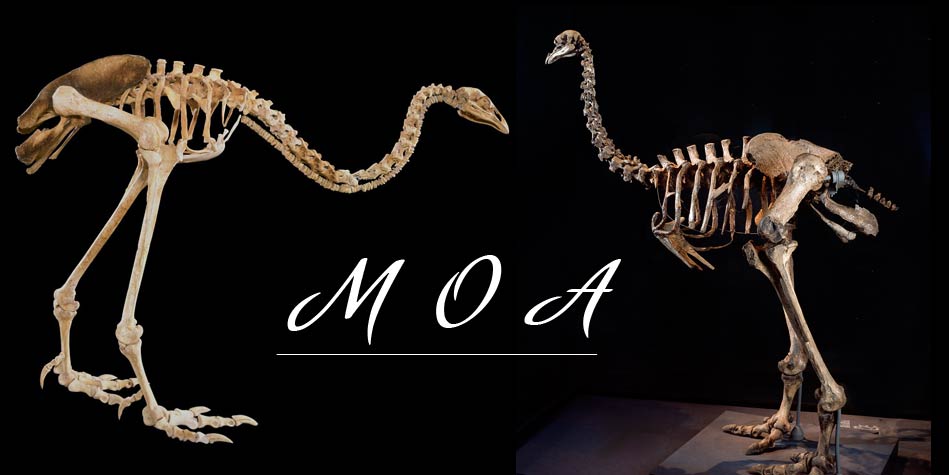

Neck – vertical or horizontal?

Most pictures represent moa with the neck upright, vertically built, however found cervical vertebrae indicate that the head was pointed to the front, as in case of kiwis. The spine attachment to the base of skull suggests that the bird walked with the neck parallel to the ground, which allowed it to reach the lower vegetation, including grass, but also allowed to lift the head to acquire food from the higher located tree branches.

Extraordinary sounds

The trachea was supported by many small bone rings. At least two genera: Emeus and Euryapteryx were distinctive for the impressive length of this organ (up to 1 meter), which formed a loop inside the bird’s body. It is the only known ratite with such feature, de facto distinctive for other groups of birds, including swans, cranes and guineafowl. This allowed moa to emit deep, extremely loud, resonating vocalizations (sounds).

Outline

In terms of outline it was similar to an emu, yet it has not been fully confirmed. The wide foot was equipped with 3 toes, while the 4th little toe was located in the rear part of the tarsus. Depending on the source it is believed that the feathers were rough and fluffy, or silky smooth. Nevertheless it is known for certain that females were larger than males. The largest female bird measured about 2 m (6.56 ft) and weighed above 250 kg (551.15 lb), although some species were smaller than a turkey.

10 years of adolescence

Contrary to the bones of all present-day birds, some found remains of moa birds revealed the growth rings similar to those on tree trunks. This hint from Mother Nature indicates that moas grew over a very long period until they reached the adult size.

All present-day birds reach their full size after only 12 months, while moa needed about 10 years.

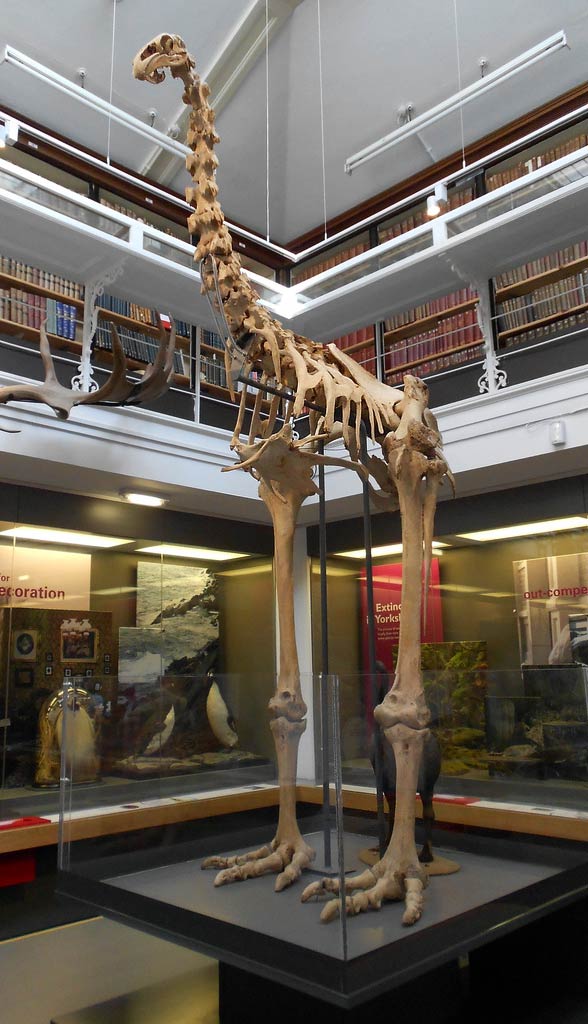

Mighty strong legs and no wings

Moas had truly athletic legs, yet they had no wings, even in the most residual form. The lack of wings suggests that it also had no breast muscles.

Feathers

Based on the found feathers it has been established that the feathering was russet, accented with black and white spots. Some feathers could have a yellow stripe.

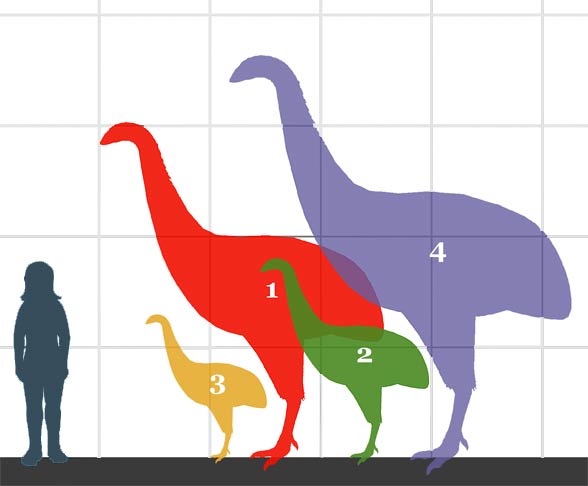

Size

The bird, depending on the species, was from 0.9 to 3.6 m (2.95 to 11.80 ft) tall, and weighed from 14 (31 lb) to even 236 kg (520 lb). The beak was short, head small and the neck was substantially elongated. The whole body, including upper legs, was covered with feathers.

Diet

The dietary habits are quite well-researched, as several coprolites and fossilized stomach contents were found. The composition of its diet was also suggested by the shape of its skull and beak. As it turns out, this giant flightless bird was a herbivore – it ate the fibrous leaves from low tree branches and shrubs.

Pachyornis elephantopus was a species which beak was similar to pruning scissors and was used quite similarly, as it allowed the bird to cut through the leaves of New Zealand flax and branches at least 8 mm (0.31 in)wide in diameter.

As many other birds moa also swallowed stones (gastroliths), that aided digestion and allowed it to regularly consume thick plant material. The stomach of a single bird could hold even several kilograms of rounded stones, about 110 mm (4.3 in) long.

Breeding

Conceivably, moa built nests and laid eggs in them, as an aggregation of egg shells was found – it could be a confirmation of moa’s ability to build nests.

Hatching and nests

The hatching season lasted from the late spring until summer – this was confirmed through the finding of seeds and pollen in the coprolites near the preserved plant material used to build structures that resemble nests.

Moa’s eggs

The eggs’ size ranged from 120 – 240 mm (4.7 – 9.4 in) of length and 91 – 178 mm (3.6 – 7 in) in diameter. Most species had white eggs, but Megalapteryx didinus species had blue-green eggs (like cassowaries).

All of them had one thing in common – the shell was very thin, which suggests that incubation was the lighter females’ duty.

K – selection strategy

Based on the bone growth rings analysis it has been established that moas, like the largest flying bird ever Argentavis, they followed a K reproductive strategy, as many other large birds of New Zealand. This means that they had a relatively low reproductive rate, and the period until sexual maturity was very long (about 10 years). An ecosystem without land predators surely contributed to the choice of such strategy.

A unique ecosystem disrupted by the Maori

Moa inhabited the New Zealand’s islands completely isolated from the rest of the world and their habitat lacked land predators. The population of birds (not only moa) was enormous, as without the predators there were no natural means of regulation of the herbivore population. In this type of ecosystem the birds could take their time until they reached maturity (K – strategy)

Today, in ecosystem ample with predators, the birds must grow up fast to have better chances for survival. Obviously the larger the potential prey is, the less natural enemies it has.

Multiple bird species in New Zealand

The long term isolation and few land mammals resulted in the creation of a unique ecosystem dominated by about 245 bird species.

Maori as a reason for the moa’s and Haast’s eagle’s extinction

The newly arrived Maori people proved to be an (un)natural enemy, a truly destructive force, which in the 13th century began to hunt for moa in New Zealand as a basic food source.

The intruders inhabiting the coastal encampments were overproducing food, killing too many birds which resulted in wasting of about half of the hunted meat.

Furthermore, in the period of the most active hunts there was a massive fire which devoured the forests of North Island inhabited by about 10 000 birds. In the late 15th century the moa was finally eradicated, which was followed by the extinction of the Haast’s eagle.

Detailed characteristics / size

Moa (Dinornithiformes)

- Height to back : 0.9 – 2 m (2.95 – 6.56 ft)

- Height with the neck outstretched: up to 3.6 – 4 (?) m (11 – 13 ft)

- Weight: 14 – 236 kg (31 – 520 lb)

- Speed: 3 – 5 km/h (1.8 – 3 mph)

Among the largest species females were 150% taller and 280% heavier than males, which is the reason for many females being classified as separate species.

Moa (Dinornithiformes) – interesting facts

- Moa lived even in the prehistoric continent of Gondwana.

- Kiwi is said to be its closest cousin, yet recent studies show that this giant flightless bird is closer related with the emu (Dromaiidae), cassowaries (Casuariidae) and South American tinamous (Tinamiformes).

- Analysis of length between the moa’s footprints indicates that the bird walking speed ranged from 3 to 5 km/h (1.8 – 3 mph).

- When Europe first heard of moa, a multinational moa frenzy occurred. At that time moa has become New Zealand’s national symbol, whereas the islands earned a new name – Moaland.

- The most recent studies suggest that the process of moa’s extinction did not last several hundred years, in fact it more likely lasted less than 100 years.

- Some museums still have the elements of soft tissue that belonged to moa stored, including muscles, skin, feathers that were naturally conserved (dried), provided that the animal died in a dry place e.g. a cave ventilated by dry winds. The majority of found soft tissue was unearthed in the steppes of central Otago.

- Conceivably the bird defended itself through dynamic kicks, as cassowaries do.

- A fake image of moa chasing a tourist in New Zealand has caused common confusion. Many people believed that moas were still alive and that they were to be feared when visiting New Zealand.

Recommended

- Extinct animals

- Elephant birds

- Haast’s eagle

- Indricotherium

- Mammoths

- Elasmotherium

- Archaeopteryx

- Sarcosuchus

- Deinosuschus

- Largest eagles Top10

- Largest birds of prey Top10

- Animals & dinosaurs records

- The fastest animals – Top 100

- The fastest birds – Top 10

- The heaviest dinosaurs – Top 10

- The longest dinosaurs. Sauropods Top 10

- The longest predatory dinosaurs. Theropods Top 10

- The heavies predatory dinosaurs Top 10

- The longest and largest ornithopods

- The longest and largest ceratopsians

- The shortest sauropods

- The smallest dinosaurs – Top 10

Im waiting for Megaloceros !

Megaloceros will be soon.